Numlock Awards: The Oscar Bait era is over. The Oscar Chum era is here.

Why Oscar Chum is ruining the Oscars, and how to fix it.

Numlock Awards is your one-stop awards season newsletter. Every week, join Walt Hickey and Michael Domanico as they break down the math behind the Oscars and the best narratives going into film’s biggest night. Today’s edition comes from Walter. We’ll have one more edition this year, the mailbag, send an email to awards@numlock.news with thoughts!

Oscar bait. We’ve all seen it. A studio out of other options tries to pretend their melodrama is the movie that will heal a broken nation. A filmmaker who desires prestige takes on a project from a filing cabinet labeled “misery porn,” ideally set in Fúczstħizberg during nineteen thirty bad. An actor starts learning an accent, takes a role from the leeward side of the socioeconomic bell curve, cracks open the DSM, or attempts to dial in on the precise level of adversity or disability so that their peers will deem their performance worthy.

For years, this was the way that studios strategized to get Oscars: shilling overwrought performances with gauzy scripts and gratuitous directing in movies lab-created to appeal to The Academy. Perfected at a sophisticated research facility later known as Miramax National Laboratories, you know the movies and the performances I’m talking about: The King’s Speech, The Reader, The Danish Girl, Life Is Beautiful, War Horse, The Imitation Game, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. The strategy was simple: ensnare the votes by going for the heart.

That era is over. Oscar bait just doesn’t work anymore. Sure, some movies will go for the playbook — Green Book feels like a recent victorious example — but we’re past bespoke, individually-crafted Oscar pitches handcrafted by artisans desperate for a nomination. We’ve gone industrial, baby.

The era of Oscar Bait is over. The era of Oscar Chum is here.

On Oscar Chum

I argue Oscar Chum is the phenomenon where movies at the Oscars get a ton of nominations in categories where they present no actual chance of winning simply because they’re a Best Picture contender, thus crowding out actually interesting and worthy nominees.

The math is basic: you only need a few dozen votes to get an Oscar nomination in certain branches, and the campaigns realize that. A big stack of nominations is enough to keep your job, even if it’s never enough to actually get a win. So you compete hard in lots of categories and hope if you can crank up the baseline name recognition high enough, that you can bag enough votes in smaller categories to run up the nominations scoreboard.

This works, because if every dollar of your marketing expense goes to elevating one single film, you’re talking just 88 votes to get a writing nomination, just 92 ballots to get a sound nomination, merely 67 to get a song nominated, and just 66 votes to get an editing nomination.

This only really works if you put all your resources into one film that can carry in all the categories, and so lately, we’ve had a phenomenon where studios will pick one movie, specifically one movie that can compete in pretty much every category, and then will push it as hard as possible to try to get as many nominations as possible.

There were ten Best Picture nominees this year, and every single one of them had a different distributor. Sure, Conclave’s Focus Features is owned by Wicked’s Universal, but the point stands: do you have any idea how hard that is to do in a country where there are only five major studios? Ten years ago, in 2015, Fox was running Brooklyn, The Martian and The Revenant against each other in a field of eight movies. We used to be a proper country.

Earlier this year, I wrote about why Emilia Perez was never actually the frontrunner. I wrote about how it’s emblematic of this shift. If Oscar bait is a knife in your heart, Oscar chum is a shotgun to your ballot.

Here’s how I described some of the more obvious ways this strategy has manifested over the past several years:

Let’s say you’re a hypothetical company called Qwikster and you’re new on the scene and you want to make a big splash. You have a very considerable awards budget, but you also (as a result of your business model) have an incredibly cutthroat and probably accurate understanding of your typical slob’s attention span. As a result, you really want to run one and only one movie as the flagship of your Oscar campaign, but you want to make it impossible to avoid, and compete in every category.

You’d probably want a visually splashy flick (to get you those below-the-lines), lots of worthy stars (there are four acting categories! Four!), with distinctive music in it (the music branch is capable of nominating songs that couldn’t even get optioned for elevators) and hell, if you can also run it for Best International that’s a freebie. Run up the scoreboard, a bit; after all, you have friends in lots of branches, you can get the noms.

Does it work? It gets a lot of nominations, yeah, and in a metrics-focused campaign that’s probably good. But does it win? Fuck no, ask Mank, Roma, The Power of the Dog, The Trial of the Chicago Seven, All Quiet on the Western Front, The Irishman — and those are just the Netflix ones.

The effect is that a higher and higher share of Oscar nominations are going only to the most popular movies, particularly the ones outside the most- or second-most-nominated pictures. Good-performing movies are getting better at scooping up nominations on the margins, at the expense of niche movies.

How do I spot Oscar Chum?

Oscar Chum can best be understood as those little strategic moves that add up the nominations scoreboard.

Not all the tricks are new. Category fraud, when a lead performance parachutes into supporting for the specific strategic reason of not wanting to run against a co-lead, has been around for some time now. (See: Brad Pitt in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, most of the supporting performances from this year, the fact that this category is now Best Leading Actor Who Is Running In A Slightly Easier Category So They’re Not Competing Against A Co-Star.)1

Think about all the times that an adaptation of a musical adds a terrible little song to pad out the scoreboard, shitty little ditties like “Learn to Be Lonely” from Phantom of the Opera or “Suddenly” from Les Misérables. On the same token, how many Original Songs are jammed into the credits where people don’t need to bother listening to them? Heck, Dianne Warren has been relegated to that end credits slot so long she could start charging rent when anyone else does it. The category is shameless for this kind of chum to pad out the scoreboard; I could not hum the tune to nominee “This Is a Life” from Everything Everywhere All At Once if you offered me ten thousand dollars, and I liked that movie.

When a short film — animated or otherwise — has a big-named nominee like, say, Wes Anderson or Riz Ahmed or Kobe Bryant or Questlove or John Lennon’s kid, well, that just does feel a little bit unsporting. Or when a major studio like Pixar pushes their short over a bunch of rivals that paid for their short with lunch money, just seems a bit off, no?

Some of the tricks do feel new, though.

Have you ever seen a For Your Consideration ad these days? I get these are industry documents, but it’s not enough to pitch a performance for a film, or one or two crafts; they pitch every one they can, in every category they can, regardless of quality. The whole movie runs as a big, massive slate, like it’s a primary in New Jersey.

Lots of movies sounded amazing this year. It’s weird that four of the five Sound nominees were also up for Best Picture. It’s a bit peculiar that only one movie, The Wild Robot (also nominated for Best Animated Feature), had good sound but wasn’t one of the ten best movies of the year. The best-sounding movies I heard this year were probably Dune, yeah, but then I Saw The TV Glow, maybe Twisters, I mean A Quiet Place: Day One required immense restraint, Civil War was a feast. But none of them had a chance, because contenders are all-in on the Oscar Chum strategy, so Emilia Pérez got a nomination instead.

Don’t believe me? The proof is in VFX, and in Makeup & Hairstyling. The Visual Effects and Makeup categories aren’t run like the other categories, they famously do a bake-off where shortlisted movies are nominated after hosting a day-long industry event, and the professionals pick the nominees after seeing directly what went into them. You may also observe that they actually pick fascinating nominees, off-beat from the best picture nominees. In the past five years, in VFX just 6 of 25 nominees also had a Best Picture nod, in Makeup and Hair it’s just 9 of the past 25. That’s nominating your craft, not nominating a slate. Compare that to other categories that are subjected to a downballot campaign: in Production Design 18 of the past 25 nominees were also up for Best Picture, in costumes it’s just over half with 13 of 25, in Editing it’s 24 of 25, in Sound, 17 of 25 nominees, same for Original Score.

And again, in VFX, in the past ten years just 11 of 50 were also Best Picture nominees. That’s what happens when you build a system that tries to honor specific people who succeed in your craft, not just vote the Netflix slate.

Michael will eternally give me crap for liking Best Supporting Actor as a category. Did you know that since 2009 — when Best Picture expanded beyond five nominees — there has just been one Best Supporting Actor winner who wasn’t in a Best Picture movie? Did you know that during the prior 30 years, you were talking nearly fifty-fifty of honoring a Supporting Actor winner who wasn’t in a Best Picture?

Obviously more nominees means more of those cusp movies get nominated, but end of the day, the Academy likes to nominate a slate and so the studios like to run a slate, so worthy acting performances disappear. We watched that happen in real time this year.

Performances and accomplishments from movies that don’t compete elsewhere don’t get far, or are deliberately spiked in favor of the (literal) bigger picture. Did you wonder where Challengers went? Well, Zendaya was running for Dune and Luca Guadagnino was running for Queer, and Amazon MGM was pushing Nickel Boys, so who precisely cares about Challengers? Speaking of Dune, you might recall Timothée Chalamet appeared in that, if you can think about his pre-A Complete Unknown career. Don’t believe me? You saw this happen in real time this season: Sebastian Stan won a friggin’ Golden Globe for A Different Man, and then used his speech to shill The Apprentice, because that movie ended up having more juice. And it worked! He got the nomination for The Apprentice!

Individually, these are all just tactics, one-off decisions made by individual campaigns to advance their own interests. But in the aggregate, those tactics become a strategy, and when everyone starts adapting that strategy, that strategy sure feels like it’s strangling these awards.

Oh, right, this is a data newsletter

So what, Oscar campaigns have learned they can more efficiently spend finite resources by picking one movie as the workhorse for an entire studio’s aspirations rather than actually running individual campaigns for worthy contenders. Big whoop, right?

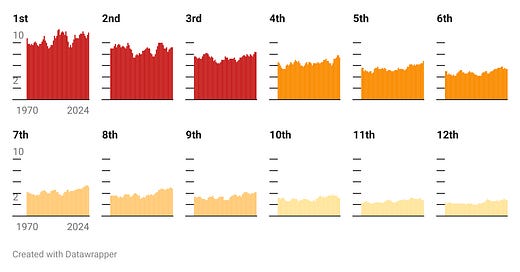

Well, I don’t think so. I think movies with well-oiled campaigns are vulturing Oscar nominations from worthy films that are not contending for Best Picture. You’ll observe that the average number of nominations per film are sharply up:

I contend that this might be a thing that’s hurting the Oscars. I think that a key problem with the Oscars viewership is a bad case of “all the eggs are in one basket,” and then when you have a mediocre (or less popular) Best Picture slate the whole enterprise is screwed. And I think if you give people chances to root for movies and performances that exist outside that top tier, you give them a chance to draw new eyeballs, especially for popular genre films.

Here’s a fun chart that both illustrates how silly some of the early Academy Awards were in terms of nominations counts. I want to draw your attention to the most recent data; you’ll see some year-to-year variation (owing to the dynamic number of Best Picture nominees, starting with the 82nd Academy Awards) and then a slight dip in total number (because they combined Sound into one category) all while the otherwise stable number of nominated films has dipped to the low 50s.

I want to talk a little bit about the one-nominee films. Inherently, you’re going to get about 20 of them per year baseline (three categories of shorts, one documentary, very little overlap there with other categories) but also keep in mind you’ve got five foreign-language too, so table stakes your baseline is between 20 and 25 in categories that rarely compete elsewhere. From that perspective, we’ve cut down the number of non-doc, non-short, non-foreign language movies with a single nomination down to the bone:

So, here’s what’s got me a bit worried.

Let me break down all Oscar nominated movies in the history of the Oscars:

2,930 films (56.5 percent of all nominated films) got one nomination and lost.

903 films (17.4 percent of all nominated films) got two or more nominations and lost them all.

557 films (10.7 percent of all nominated films) got one nomination and won.

438 films (8.5 percent of all nominated films) got two or more nominations and managed to win exactly one Oscar.

355 films (just 6.8 percent of all nominated films) won more than one Oscar.

I bring this up because for the majority of movies, you have one nomination, you lose it, and it’s an honor to be nominated. This is all things considered a pretty solid night, I’d argue the best night you can have without winning an Oscar. And this group of nominees is getting devoured by movies that get lots of nominations and lose them all, or get lots of nominations and only walk away with one or two pieces of hardware.

I want to talk about a very specific subset of movies: movies that lost five or more Oscars without winning five Oscars. This set of movies is interesting, because I believe it encompasses a lot of Oscar Chum, even if it picks up a few movies that were just pretty good in the wrong year. The five-win bar excludes movies that got a lot of nominations and still delivered, while the “lost five Oscars” means that it was all over the categories either way.

In the grand history of the Academy Awards, 6.3 percent of movies lost at least five Oscars without winning five Oscars. From the 70th Academy Awards in 1998 through the 89th Academy Awards in 2017, that figure is 6.6 percent, as far as I’m concerned right on the money.

But in the eight most recent Oscars, from the 90th through 97th, 10.7 percent of movies lost five without winning five. That rate isn’t double the typical rate, but it’s 70 percent higher than normal, and the best I can get to an argument that bloated nomination counts for highly-touted movies are consuming more than their historical share of nominations, at the expense of smaller movies who in a previous Oscar regime would get one or two nominations.

In total, those 39 films racked up 324 nominations, and averaged just 1.33 wins despite 8.3 nominations, which sounds like the catch rate when you’re just chumming the waters to me.

I got bored during the numbers part, just tell me what to do, nerd.

The Oscars are an election. They’re just people. And they’re subject to the same biases and strategies, that is, until they aren’t anymore.

We saw Oscar Bait rise. We saw it work, we saw it get rewarded. But then we noticed it. We named it, and called it Oscar Bait. We mocked it, in Tropic Thunder, in For Your Consideration, in the 30 Rock joke of Tracy Jordan’s Oscar-winning performance in Hard to Watch: Based on the Novel “Stone Cold Bummer” by Manipulate.

And then it stopped! At least for the most part, really. Once it became named, and spottable, voters stopped rewarding it as much.

That’s what I want for Oscar Chum. Next year, there will be a few studios that push one movie and one movie only. Maybe you’ll get a prosaic modern drama making a serious case for Costume or Production Design just because the boss is up for director. And hey, I know this is out there, call me crazy, but who knows, maybe a movie will split up their actresses into senseless separate Lead and Supporting divisions even though it’s an obvious two-hander and the original Broadway cast had the courage of their convictions to both run in Lead, even if it meant one lost.

Don’t reward it.

Identify the chum, and don’t fall for the chum.

Critics, so much of what you do is setting the terms for the rest of the season, do not give in to category fraud, stop it at the Globes. Guild voters, elevate work that you find interesting, not just work that is popular. Oscar voters, only you can prevent Oscar Chum: go out of your way to vote for colleagues in roles outside of the main slates, and at this point I would go so far as to encourage you to advocate for your branches to follow the lead of the VFX and Makeup & Hairstyle branches in pursuing a bake-off shortlist.

It’s very, very hard to make the Oscars an interesting show by only tweaking Best Picture nominees, and I think mathematically that’s a trap. It doesn’t take a lot of ballots to get a worthy contender nominated in other categories, so make the Oscars bigger and more exciting by going outside the box.

Join me, and we can make Best Supporting Actor actually interesting again.

This isn’t even unique to acting: movies love to sabotage what they consider to be secondary contenders in song, remember when the smash-hit song “We Don’t Talk About Bruno” from Encanto wasn’t even put up by Disney, only for “Dos Oruguitas” to get smoked by “No Time To Die”?

Though I only watched one of the best picture nominees this year, I love reading all of your Oscar content and come out feeling like I'm far more cultured! This is fantastic work - thank you for all your analysis and work writing it.

Curious how many votes a documentary needs to get nominated and whether you’re seeing a similar phenomenon in that field.