What awards are getting better at predicting the Oscars?

Numlock Awards is your one-stop awards season newsletter, and it’s back! Every week, join Walt Hickey and Michael Domanico as they break down the math behind the Oscars and the best narratives going into film’s biggest night. Today’s edition comes from Walter.

As we ease back into the season, I wanted to take a few steps back and look at how, overall, the weights with which I assign the different precursor awards value have been shifting over time.

Back when I was at FiveThirtyEight, the model looked at the performance of a given precursor award over the previous 25 years. If it got it right in 10 of those years, its baseline score before adjustments was 0.4, if it got it right in 15 of those, it was 0.60, if it got it right in all of them it was 1. Basic stuff.

However, after I left and did a refresh on the math underlying the model I decided to make a key change: given the speed at which the composition the Academy was changing and adding new members, I determined it would be a mistake if the events of 1994 had the same weight as the events of 2019. So I tweaked the ratings: the model looked at the past 20 years, and the past five years are weighted three times as much as the first ten years, and the events of six to 10 years ago are worth twice as much.

So for this years Oscars, the data in the model will weight the 2001-10 Oscar season even, the 2011-2015 Oscar season two times as much as those, and the 2016-20 Oscar season three times as much as the 2001-10 awards.

The goal of designing things this way is to make the forecast reflect changing fundamentals quickly, rather than being stuck in the past. The input data is still the same — precursor awards remain the best way to discern the state of the race! — it’s just how we value it that I tweaked a few years back. The previous iteration of the model would only be able to shift a baseline score 4 percentage points one way or another year over year, which was perfectly fine when the size of the Academy was pretty much unchanged year-to-year. This newer, what-have-you-done-for-me-lately model can roll with the punches a little more deftly.

All that being said, I ran the weighting calculation over the past ten years of data, just to see how the baseline weighted average performance — before I square it and double it if it’s a guild, just the straight-up weighted average underlying the entire model — has shifted over the past decade.

Lead acting prizes

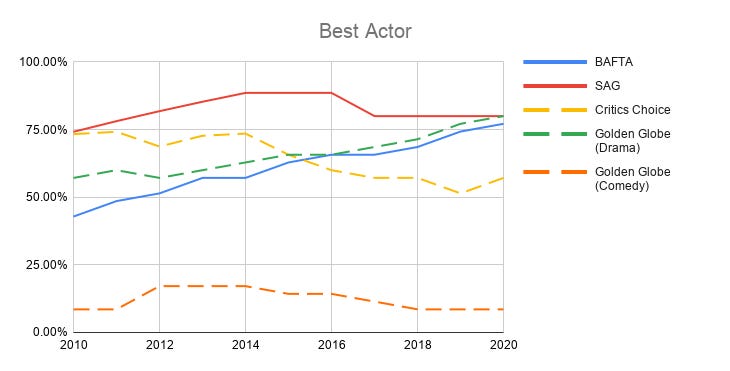

What we’re looking at here it the weighted percentage of the time that a given precursor award — like the Screen Actors Guild award for Best Actor — coincided with the same performer winning the Oscar. The weighting is on more recent events, so lines that go up mean that the precursor is getting more predictive, and lines that slope down mean the precursor is getting less predictive.

The three most surprising things I see here are:

The BAFTAs are getting more and more reliable year over year. It’s by far the most interesting thing in this entire analysis, and I’ll be coming back to it again below.

The Critics’ Choice is losing its luster. For Best Actress, it’s been a reliable coin toss, which is not bad in the slightest — correctly predicting the Best Actress winner half the time is quite good! I bet if I, Walter, personally predicted the winner of the Oscar the night before the Critics’ Choice I’d do much worse than that! But in Best Actor, the critics are losing their grip a bit.

On the other hand, the Globes Best Actor (Drama) category has gone from “fine” to damn good over the course of the past decade. I have my suspicions as to why we’re seeing the Globes and the Critics’ Choice change places — the viewing audience for the Globes is much, much higher than that of the Critics’ Choice, and as the Academy expands that kind of campaigning I believe has become more effective — but it’s a shocking twist for me, a guy who has dismissed the Golden Globe as a paperweight for a decade now.

Best Supporting Acting categories

The one thing I love in these is, compared to the Best Lead categories, there has been an unmistakable tightening:

In these prizes, the four main precursors have gone from “bit of a crapshoot” — between 40 percent and 70 percent reliability depending on the prize and the year — to “precise, if not always accurate.” That is to say, all of them basically get it three out of four times, give or take. The floor has gotten higher.

I fear with these that the number of precursors is sufficiently low that it’s much easier for one contender to win 2 out of 4 or 3 out of 4 and become the odds-on-favorite. Like, were someone to win both the Critics’ Choice and the Golden Globe, for a lot of people that race is pretty much over. While in the lead categories, with the Globes split up, it’s harder to speak as decisively.

Either way, the most remarkable thing is that not a single precursor prize appears to be getting worse. They’re all either holding the line or materially improving. It’s spooky.

Best Director

The only thing I’m really seeing here is some fluctuation with the pair of critics awards and just the BAFTAs stomping recently. This is all the more interesting to me because the last time a Brit won Best Director at the Oscars was 2010, and only two have won since 2000, so it’s not like BAFTA was just dealt a favorable series of hands. Something’s going on with BAFTA, we’ve seen it in nearly every category so far.

Last thing I’ll remark on is that the DGA is still doing fine. They’ve had whiffs, but the levee hasn’t broken, at least not for Best Director.

Best Picture

This is what I mean when I say that everything is changing and the only thing the model can do is hold on tight and wait for the Academy to stabilize:

Look at that!

The four big reliable precursors — BAFTA, SAG, PGA and DGA — are either holding it barely together (SAG, PGA) or in abject free fall (DGA, BAFTA) in terms of accurately calling the eventual Best Picture winner.

The DGA has gone from in lockstep with the Academy to a coin flip, a breathtaking uncoupling that’s the result of consistent mix-ups in the past few years, correctly calling Best Picture only once in the past five seasons. The DGA has gone from being the most plugged-in people on the Best Picture awards circuit to increasingly out-of-touch. It’s wild.

They’re not alone: with two modest exceptions, every award is worse at predicting the Oscars than they were 10 years ago. Major shifts in the electorate will do that to you.

Anyway, I guess I wanted to start us off by looking back and seeing just how much harder this is getting. The advantage is that by design, the model is self-correcting, and it still holds up pretty well under pressure all things considered. That said, this year’s going to be weirder than ever, as the lack of physical campaigning makes the internationally broadcast precursor prizes more important than ever in terms of getting the word out.

This week we get Golden Globe nominees and SAG nominees, so relish the uncertainty because it’s not going to last much longer.