Numlock Awards is your one-stop awards season newsletter. Every week, join Walt Hickey and Michael Domanico as they break down the math behind the Oscars and the best narratives going into film’s biggest night. Today’s edition comes from Walter.

Tomorrow night — or, from an American perspective, tomorrow afternoon — is the BAFTA Awards, and they’re one of the most interesting precursors we got and it’s worth a closer look. The British Academy is an outstanding test case for the Oscars because they’re so much like the Academy itself, not a union or a critics’ group but your standard “we invited everyone in the industry we think is good and we let them vote on stuff” body.

Historically, you could do pretty well for yourself looking at the BAFTAs and filling out an Oscar prediction ballot. That’s changed. They’ve developed a few idiosyncrasies that make their tastes distinct from the Academy voter base. For whatever reason, they have become absolutely godawful at picking the eventual Best Picture.

I really love this chart. It defies explanation. You’ve got an award show that can increasingly reliably predict every category except Best Picture, where it has been reliably getting worse for a decade. It’s downright impressive.

It’s so paradoxical, I am only able to express my feelings like so:

So needless to say, it’s a big night for the acting and directing races, and informative when it comes to Best Picture.

The primary explanation I have is that BAFTA selects all of its winners through first-past-the-post style elections. For all their elaborate nomination systems, at the end of the day whichever has the most votes wins. A winner doesn’t need to have a majority to win, and there are no ranked-choice ballots.

This is, obviously, how most voting works. It’s how the Academy votes on every single category except, you guessed it, Best Picture. There, the Academy votes based on a ranked-choice ballot system, meaning that the film that leads in the first round of voting will not necessarily be the one that eventually wins.

This could explain why the BAFTAs are very good at explaining the acting and directing prizes but not the top prize. It’s not that the BAFTAs don’t have similar taste in the best film of the year, it’s that the Oscars tabulate taste differently, rewarding the films that garnered a majority appeal.

So if we know why BAFTA is somewhat bad at predicting Best Picture, why was it ever good at predicting Best Picture?

That, I do suspect, has a large part to do with the expansion of the Academy, and the unlikelihood that BAFTA has grown in a similar way.

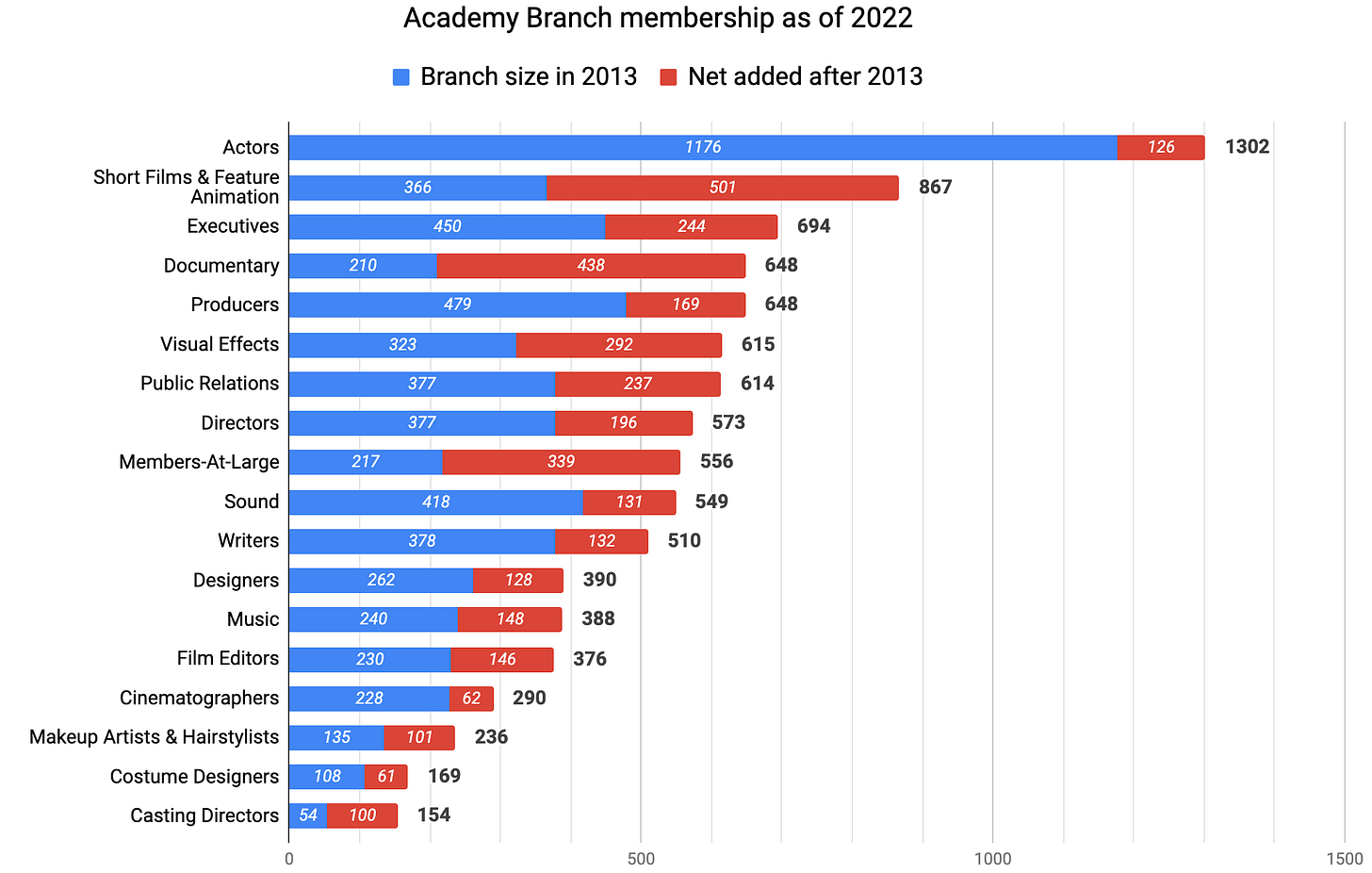

I have written and talked before that the real story of the Academy expansion has been in below-the-line categories, but in particular it’s been international, with AMPAS boasting that lately about half of the new members were from outside the United States.

The BAFTAs can’t expand out. It’s not impossible for non-U.K. folks to join the organization, but it’s not as easy as just an invite. To be eligible, one needs to be a British citizen, or a BAFTA winner, or work for a UK broadcaster, production company, or “Made a significant overall creative contribution to the global film, games or television industries” which is squishy enough that they can probably get some truly great overseas talent in but again, that’s not really what they’re there for.

So in short, I think the BAFTAs are really interesting. I think they used to predict Best Picture because they resembled the Academy enough that the first-past-the-post versus ranked-choice voting difference didn’t really mean all that much. Then, BAFTA and AMPAS began to grow apart, with AMPAS growing in ways BAFTA was simply unable to. That’s when we began to really see the first-past-the-post versus ranked-choice voting difference become a big deal. Hence, a body that can predict all the parts, but not the whole. An organization with very similar tastes to AMPAS, sure, but not a way to reliably express that taste in a predictive manner at the top.